General Grammar vs. Universal Grammar: an unbridgeable chasm between the Saussureans and Chomsky

As Harris (2003: 152-170) has illustrated -especially by his concentration on the notion of 'creativity'- 'Chomsky the Saussurean' is nothing but "an academic fable". This fable is a result of misreading -by Chomsky himself (1964) and also by others- of Saussure's la langue (in the singular form) as generativist concept of 'competence' and, therefore, its grammar as the Universal Grammar (UG).

Chomsky's approach to the deviant utterances in his standpoint of individual psychology never brings him to a concept of 'grammar' the function of which is also to explain the poems, the puns and any kind of wordplay. The contradiction here is that, on the one hand, he demands just to speak about 'individual faculty of language' (which can lead to an infinitive number of individual grammars), and on the other hand, his aim is to discover the UG which means "a framework of principles and elements common to attainable human languages" (Chomsky, 1986: 3) (which for him would be a concrete unique absolute one). Such situation leads him to assume a completely transcendental postulate which claims that all human beings share an innate, genetically determined language faculty that contains/knows the rules of UG. As a result, Chomsky and others in the huge generativist camp put their attempts to seek a vouchsafed 'universal rule-and-concept system' which is a reproduction of an old traditional dream of 'universal language of thought'. In a Saussurean perspective, this assumption, aside from its failure to observe the diversity and specificity of languages, is a metaphysical and, therefore, an incoherent base for linguistic theory.

Basing linguistic theory on language acquisition or biological facts is not at all acceptable for Saussure because any understanding of the faits de parole and 'substantive facts' premises an understanding or an implicit definition of language which is in Chomsky's case the common modular understanding of language. The generativist modular conception of language, therefore, turns a deaf ear to the fundamental problems being propounded by Saussure concerning the very essence of language, especially the arbitrariness of linguistic sign.

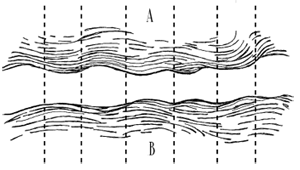

How does Saussurean linguistics define its own grammar as General Grammar, and how does it deal with the common or universal linguistic facts which are the main goals for the Chomskyans? This is a main concern in the present study, which I intend to consider as a matter of 'algebra of language' and also as a question of typology by investigating the few indications by Saussure in the CLG and ELG and the explications by Hjelmslev. In this regard, we will see there are only the universal arbitrary structural rules just for seeking a general framework/calculus susceptible to describe all possible languages and language types.

Finally, in agreement with Harris and De Mauro, we will claim that the Chomskyians and the Sausureans are in two fundamentally different paths in dealing with grammar, where the latter -and notably Hjelmslev- provides a broader possibility for theorizing language.

Publication version PDF